During the Great War, the United States went to great lengths to stop people from expressing their views on the war and the draft. According to historian Sean Dennis Cashman, Wilson said that war "required illiberalism at home to reinforce the men at the front. We couldn't fight Germany and maintain the ideals of Government that all thinking men shared...once led into war, [Americans] will forget there ever was such a thing as tolerance" (505).

So, in order to set Europe free from tyranny, the government had to restrict more of Americans' rights. Historian Howard Zinn has written at length that part of this suppression was done to keep Americans from expressing their anti-war sentiments/feelings:

- Why should we get into a war that we have no interests in? This is only about European colonialists, not U.S. interests;

- Why should I be drafted to go protect France or Belgium? (only 73,000 volunteered in the first 6 weeks after Wilson declared war on Germany in April 1917);

- Why should we spend millions and millions of our tax money to do this?;

- Why should we join a war that current French soldiers are beginning to mutiny against? (in essence, why we should we join a losing fight?);

- Why should we break away from our tradition of isolationism? It's served us well for this long (if it ain't broke, don't fix it);

- If I am a soldier of color, why should I go fight for a country that wants to preserve democracy abroad but doesn't treat me like I deserve democracy at home?

So Wilson and Congress together got tough on this kind of anti-war talk and anti-draft interference w/ the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918. The Supreme Court affirmed that we do NOT have the right to free speech as long as it creates a "clear and present danger" (much like yelling "FIRE!" in a crowded theatre like Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes jr. so eloquently phrased it in the 1919 court decision, Schenck vs. U.S.). Under these acts, a person can be fined up to a max of $10,000 (almost $220,000 in 2023 dollars) and given a 20 year sentence for interfering with the sale of war bonds or the draft, or saying anything profane, disloyal, or abusive about the government. Obviously, these laws violate the 1st Amendment. But is sacrificing those rights vital to the American war effort?

A speech like this one by Eugene Debs is the kind of thing that got him in trouble and thrown in jail:

"Wars throughout history have been waged for conquest and plunder. ...the

working class who fight all the battles, the working class who make the supreme

sacrifices, the working class who freely shed their blood and furnish their

corpses, have never yet had a voice in either declaring war or making peace. It

is the ruling class that invariably does both. They alone declare war and they

alone make peace. They are continually talking about their patriotic

duty. It is not their but your patriotic duty that they are concerned

about. There is a decided difference. Their patriotic duty

never takes them to the firing line or chucks them into the trenches."

(emphasis added)

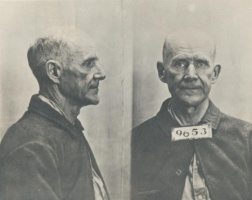

*Debs was sentenced to jail for this speech and while in jail ran for President under the Socialist Party for which he received almost one million votes in 1912 and in 1920! Website for Debs: http://www.eugenevdebs.com/

*Debs was sentenced to jail for this speech and while in jail ran for President under the Socialist Party for which he received almost one million votes in 1912 and in 1920! Website for Debs: http://www.eugenevdebs.com/

During wartime, there is a feeling that certain ideas (that question how and why things are being done) may be considered dangerous, traitorous, or even downright unpatriotic. Many have been accused of such things when criticizing their government during times of war, and our history book mentions some of them. As I mentioned above, Eugene V. Debs, a Socialist Party leader and candidate for the Presidency, was sentenced to ten years in prison and fined $10,000 for "speaking out against the war and the draft" (Danzer, et. al. 392). Anarchist Emma Goldman was convicted and sentenced for creating a No Conscription League and then was deported to Russia during the Red Scare (1919-1920) after two years in jail.

But my questions still remain:

1. Is questioning your country's conduct during a war o.k.?

2. Should asking questions about how the war is conducted, about the tactics being used (torture, waterboarding, etc.), about how the goals are being met (or if they're being met at all), or is it all worth the sacrifice of all the young men and women's lives??

3. Is this line of questioning during war time o.k. or does it make you unpatriotic? Why?

Your response to all three questions should be a minimum of 350 words total, due by Wednesday, November 1.

*Debs was sentenced to jail for this speech and while in jail ran for President under the Socialist Party for which he received almost one million votes in 1912 and in 1920! Website for Debs: http://www.eugenevdebs.com/

*Debs was sentenced to jail for this speech and while in jail ran for President under the Socialist Party for which he received almost one million votes in 1912 and in 1920! Website for Debs: http://www.eugenevdebs.com/

2 comments:

(1.) I believe that questioning your country’s policies is the right thing to do as a citizen of the country, during wartime or not. If there is a law or decree that makes it so that people are dying or are being injured in war needlessly, then there should be a movement behind changing it. In fact, the most important time to change it is during a war. This is because there are much more casualties in war and therefore many more lives that could be saved from unnecessary death. The sooner that you can help make a change, the more of a change you will have actually made.

(2.) Asking questions is the only way to ever get answers. If you question your governments’ methods, then finding a way to act on it is a great way to have your voice heard. In a war, some methods that are used are terribly gruesome and tragic. Finding a way to help stop extreme violence is a very humane thing to do. Torture and other forms of violent warfare are not only inhumane, but they also label your country as inhumane. When you are a citizen of a country that is seen as an unjust power, you are not respected either. Gaining peoples’ respect for your country is a very important factor if you want to be treated kindly as well. When you perform good actions, you will be seen as a good person. Whoever wins the war won’t remember the winning as much as what they had to do to get there. Having to trade your sanity and/or life for your country when you didn’t have to is unacceptable.

(3.) Being patriotic means that you stand for your country and its decisions. You cannot do that when you don’t even share the same ideas as your country. Fixing the country's policies only means that the country now better represents the current public. A country that can never change is a country that is forcing its people to never change as well. Patriotism should also mean that you are trying to better your country, out of love for it. You will never become patriotic if you and your country are not hand in hand.

-Zachary O'Connor (2nd hour)

1. Questioning your country during the war should be okay. Freedom of speech and freedom of the press are some of our basic rights written in the Constitution. There is the FIRST Amendment for a reason. The founding fathers thought of them first because of how important they were. That's why it is not okay for the government to be able to take them away during the war. Also, what is stopping them from taking them away during other times as well? It is not fair and right for the government to be able to take away your freedom of speech and press when you question the government's conduct during a war. You should be able to express your opinions at all times, no matter if your country is in a war or not. It is your First Amendment right.

2. I think you should be able to ask questions about war tactics and if the war is meeting its goals, but there are some things about war I don't think the public should know about. I don't think it is important for the public to know in detail how the U.S.A. is brutally torturing the prisoners of war. Or that they are actively murdering an entire village of people for answers, and more stuff like that. That is not important for the people to know, that would cause some resentment of our own country. And during a time of war, you don't want the whole country to hate the government. If some people use their rights to express their opinion that is fine, but if you give the public gruesome evidence that can turn bad. But I do think it is okay to tell the public some things. You could tell the public the reason for the war, the tactics or battle plans we are going to use, the threat the country is in, and if the war is working or not. Stuff like that isn't going to cause the people to hate the government and the war. It would make them feel more informed and more part of the war. And possibly could make them feel safer that they know they're not in danger. I think it is okay to tell the people some or most information about the war, but there is stuff that should go unsaid.

3. I think this line of questioning does not make you unpatriotic, I think it is just you expressing your opinion of the war. If you don't think helping another country in a war is useful, or even worse it might hurt the U.S. then it doesn't make you unpatriotic, some might argue it makes you more patriotic because you show you care for the country. If you are questioning why the U.S. is involved in some war or is starting a war we don't need, you are not being unpatriotic, you looking out for your country and are expressing your right to an opinion. You shouldn't be seen as unpatriotic for asking questions about a war.

Carter Hladki

Post a Comment