During the Great War, the United States went to great lengths to stop people from expressing their views on the war and the draft. According to historian Sean Dennis Cashman, Wilson said that war "required illiberalism at home to reinforce the men at the front. We couldn't fight Germany and maintain the ideals of Government that all thinking men shared...once led into war, [Americans] will forget there ever was such a thing as tolerance" (505).

So, in order to set Europe free from tyranny, the government had to restrict more of Americans' rights. Historian Howard Zinn has written at length that part of this suppression was done to keep Americans from expressing their anti-war sentiments/feelings:

- Why should we get into a war that we have no interests in? This is only about European colonialists, not U.S. interests;

- Why should I be drafted to go protect France or Belgium? (only 73,000 volunteered in the first 6 weeks after Wilson declared war on Germany in April 1917);

- Why should we spend millions and millions of our tax money to do this?;

- Why should we join a war that current French soldiers are beginning to mutiny against? (in essence, why we should we join a losing fight?);

- Why should we break away from our tradition of isolationism? It's served us well for this long (if it ain't broke, don't fix it);

- If I am a soldier of color, why should I go fight for a country that wants to preserve democracy abroad but doesn't treat me like I deserve democracy at home?

So Wilson and Congress together got tough on this kind of anti-war talk and anti-draft interference w/ the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918. The Supreme Court affirmed that we do NOT have the right to free speech as long as it creates a "clear and present danger" (much like yelling "FIRE!" in a crowded theatre like Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes jr. so eloquently phrased it in the 1919 court decision, Schenck vs. U.S.). Under these acts, a person can be fined up to a max of $10,000 (almost $220,000 in 2023 dollars) and given a 20 year sentence for interfering with the sale of war bonds or the draft, or saying anything profane, disloyal, or abusive about the government. Obviously, these laws violate the 1st Amendment. But is sacrificing those rights vital to the American war effort?

A speech like this one by Eugene Debs is the kind of thing that got him in trouble and thrown in jail:

"Wars throughout history have been waged for conquest and plunder. ...the

working class who fight all the battles, the working class who make the supreme

sacrifices, the working class who freely shed their blood and furnish their

corpses, have never yet had a voice in either declaring war or making peace. It

is the ruling class that invariably does both. They alone declare war and they

alone make peace. They are continually talking about their patriotic

duty. It is not their but your patriotic duty that they are concerned

about. There is a decided difference. Their patriotic duty

never takes them to the firing line or chucks them into the trenches."

(emphasis added)

*Debs was sentenced to jail for this speech and while in jail ran for President under the Socialist Party for which he received almost one million votes in 1912 and in 1920! Website for Debs: http://www.eugenevdebs.com/

*Debs was sentenced to jail for this speech and while in jail ran for President under the Socialist Party for which he received almost one million votes in 1912 and in 1920! Website for Debs: http://www.eugenevdebs.com/

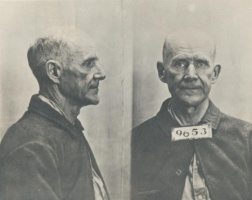

During wartime, there is a feeling that certain ideas (that question how and why things are being done) may be considered dangerous, traitorous, or even downright unpatriotic. Many have been accused of such things when criticizing their government during times of war, and our history book mentions some of them. As I mentioned above, Eugene V. Debs, a Socialist Party leader and candidate for the Presidency, was sentenced to ten years in prison and fined $10,000 for "speaking out against the war and the draft" (Danzer, et. al. 392). Anarchist Emma Goldman was convicted and sentenced for creating a No Conscription League and then was deported to Russia during the Red Scare (1919-1920) after two years in jail.

But my questions still remain:

1. Is questioning your country's conduct during a war o.k.?

2. Should asking questions about how the war is conducted, about the tactics being used (torture, waterboarding, etc.), about how the goals are being met (or if they're being met at all), or is it all worth the sacrifice of all the young men and women's lives??

3. Is this line of questioning during war time o.k. or does it make you unpatriotic? Why?

Your response to all three questions should be a minimum of 350 words total, due by Wednesday, November 1.

*Debs was sentenced to jail for this speech and while in jail ran for President under the Socialist Party for which he received almost one million votes in 1912 and in 1920! Website for Debs: http://www.eugenevdebs.com/

*Debs was sentenced to jail for this speech and while in jail ran for President under the Socialist Party for which he received almost one million votes in 1912 and in 1920! Website for Debs: http://www.eugenevdebs.com/